Matt Galloway is the host of THE CURRENT on CBC Radio One. The following is a transcript of the show on January 10, 2023, with Eli Rubenstein.

ELI RUBENSTEIN APPOINTED TO ORDER OF CANADA FOR WORK IN HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

Matt introducing: We continue our series looking at the contributions of people appointed to the Order of Canada. Eli Rubenstein is the religious leader of Congregation Habonim and the long-time National Director of the March of the Living. He has been honoured for his significant contributions to Holocaust education.

To kick off the new year we have been sharing some of the stories of the new additions to the Order of Canada. We’ve heard from scientist volunteers, musicians, teachers- and we’ll get to the teachers’ part in a moment.

It's been fascinating learning about Canadians and the work that they are doing. Eli Rubenstein is the religious leader of the congregation Habonim and longtime national director of the March of the Living. He is receiving the order of Canada for his significant contributions to Holocaust education. Eli Rubenstein. Good morning.

Eli: Good morning, Matt

Matt: Congratulations

Eli: Thank you. Thank you very much. Very much appreciated.

Matt: Well, what does this recognition mean to you?

Eli: Well, to be quite frank, when I got the phone call from the wonderful woman at the Governor General's office, my first reaction was, are you sure you have the right number? To which she laughed, and I was completely surprised, and shocked, did not see it coming. I had no idea this was being planned, that people were lobbying behind the scenes for this and saying all sorts of beautiful things about me. And so, I was completely taken aback by it.

But then I grew from that surprise and really not feeling I was worthy of it - and I'm still wondering if I am - to incredible appreciation because I was not expecting the deluge, the flood of phone calls and emails and texts and just incredible appreciation and joy and vicarious pleasure that so many of my friends expressed to me.

And that for me you see the order of Canada is a beautiful award, but the love and the affection and just the genuine good feelings I got from so many people completely took me by shock. And I think for me, what I thought about was when I got the award that there's so many, many other Canadians who are doing incredible work and deserve accolades, if not as much, even more than I. And if you're listening to this, you know such people, give them a call, give them a pat in the back and tell them how much they're appreciated because I know that they will appreciate that as well.

“When I was a little girl, I had a normal childhood like you. I even had a boyfriend. Well, it was not really a boyfriend. I liked him. He didn't like me, but that's another story. And the kids of course laughed. And then she said, I remember being dragged from my home in Hungary in Debrecen and our neighbours laughing.”

“We arrived here in Auschwitz-Birkenau. I'll never forgive myself for what happened next: I never had a chance to say goodbye to my mother. And I'm an old woman now, but I'll never make peace with the fact that I never had a chance to say goodbye to my mother. And then I moved to Canada. I began my life again. I married and had children, but the memories will always be with me. And then she looked at the students and said: please work for a world where nobody will have memories like mine ever again. Please work for Tikkun Olam. Please be my witnesses.”

Matt: It's very generous of you. Let me talk about the good work that you have done that you're being recognized for. Where did the work in terms of Holocaust education begin for you?

Eli: Well, I grew up in Toronto in a very religious community. My own mother was a refugee from the Holocaust. Many of her family members perished. My grandfather came from a town in Poland, my mothers from Hungary. My grandfather came from a town in Poland. It was virtually wiped out during the Holocaust. Not a single Jews survived. He came in 1913, but anybody who didn't come before the war, almost nobody survived from that town. And I grew up not only having Holocaust stories in my family, but also my peers. Many of my friends, their parents were Holocaust survivors. My teachers, many of them were Holocaust survivors. I grew up seeing, as a matter of course, people with numbers in their arms, which was the numbers the Nazis put on prisoners in Auschwitz, branded them like cattle. And I grew up with that very, very sad part of human history as part of my consciousness. And it was something that really, really bothered me and troubled me.

Because I was a child. I wanted to love the world; I wanted to appreciate the world. I wanted to see the beauty in the world. And then I was surrounded by examples of the exact opposite…

So, for my childhood, I was wondering how this could have happened. How can we understand this and how can we make sure it doesn't happen again? Not just to the Jewish people, but to any member of the human family. So, I grew up with that shadow of the Holocaust throughout my entire childhood and adolescence.

Matt: Part of the work that you do, as I mentioned in the introduction, is to take students from around the world with survivors to spend time in significant sites from the Holocaust and Poland and Germany.

Why is it important to be in those places? Because education can happen in any different number of ways, but when you are there, what's different about being there in terms of that educational process?

Eli: You are absolutely right. Education could happen anywhere and we should be encouraging people to read books and to watch films and to listen to speakers about the Holocaust and all. That's very good. But when you go back to a place like Auschwitz and you hear someone tell their story and a very place their tragedy unfolded, it leaves an indelible mark.

I remember Judy Weissenberg Cohen, a beloved Holocaust survivor from Toronto, telling her story. I have heard it many times, and here is just a fragment of her story. She told the students.

And hearing her tell the story in the very place that tragedy unfolded means that for the rest of the students' lives, they'll remember “I was at Auschwitz with a survivor. I remembered she told us a story about the last time she saw her mother that will never leave me,” and they will transmit that story to others in a way that you can't do from reading a book or simply watching a film. So, I think there's an incredible power of hearing the stories in very places that tragedies unfolded. And that's just one example of that.

Matt: What have you heard from those students who have heard those stories firsthand, as you say, in those places of horror?

Eli: Well, the students embrace survivors. They support the survivors and they've committed to transmitting the memory of the survivors to the next generation. And they do it in a very universal way. They say it's not just about fighting antisemitism and hatred towards Jews, about fighting against all forms of racism and injustice, and intolerance.

I should say on the trip itself, the students give incredible support to the survivors. I remember David Shentow, a Holocaust survivor from Ottawa when he arrived in Auschwitz streets as a teenager, he was standing in this selection and the prisoners were told to give up their belongings. And one man said, “please let me hold onto my family photograph.” At that moment, the Nazis sick to the dog on him, and he was killed on the spot.

When David returned with the students to Auschwitz-Birkenau and was standing at the gates, all of a sudden, he froze, he became paralyzed, and two students went on each side and said, “David, we'll walk in together with you and we'll walk out together.”

And so, the survivors tell the stories to the students, and the students give hope to the survivors because they're remembering their stories and learning the lessons and building a better world for all humanity.

And I've seen that throughout my experience that the students go off in the world, do incredible work in human rights, activism and social justice because of what they’ve seen on the March of the Living. And they are empowered by the survivors to be the witnesses for the witnesses.

Matt: In the work that you've done, you've met a number of people and you've mentioned some of them. Tell me about your interactions with General Romeo Dallaire.

Eli: Well, as I said, the universal lessons of the Holocaust are as important as specific lessons. In other words, the specific lesson is to fight antisemitism. The universal lesson is to fight any kind of intolerance and racism. And I remember meeting General Romeo Dallaire er once at a dinner, and I'm going to get the story as close as I can get to it many years ago. But it was a story that left the deep impact on me. And we all know General Romeo Dallaire one of the few people who tried to stop the genocide in Rwanda, which happened at a quicker rate than the Holocaust, if you can believe that. And one of the few people tried to stop him when he came back to Canada. He was so sad that he didn't do more yet. He was one of the few people that did anything and a true Canadian hero. And in that story, he talks about being in a village that had completely wiped out by the Hutus, and there was almost nobody left, but he came across one Tutis child that was battered, bruised, and crying, and he picked up the child to try to comfort him.

Eli: In that moment, he asked himself, what am I doing here? Thousands of miles away from home, a different country, different culture, different everything? What am I doing here?

Then he looked into the child's eyes and he knew the answer because when he looked into the child's eyes, he saw the eyes of his own children back in Canada wanting love, wanting protection, wanting dignity, wanting respect, wanting nurturing. And that's when he realized there is no difference. That's when he realized that no human is more human than any other human. And why do genocides and Holocaust happen? Because we simply haven't figured out that very, very, very obvious fact that no human is more human than any other human.

And I often say to the students, there's so many lessons you learned in the March of Living from the history of this incredibly challenging moment in human experience, but if the only lesson you get out of this is that no human is more human than other human, the ultimate infinite, dignity, of all, humanity? - that would be enough for me. So, I always remember General Romeo Dallaire’s message and I always teach it to the students on the trip and they accept the lesson.

Matt: Those students are incredibly lucky to be on a trip like that and to have that opportunity to learn. But we'll often hear stories of students, younger students who have no knowledge of the Holocaust at all, that they will be asked if they know details, and they say that they've never heard of it before. When you hear that these are regular stories. But when you hear that based on the work that you do, what goes through your mind?

Eli: It's sad to me because it reminds us of how much work we have to do, but at the same time, I do not want to give into cynicism, despair, and that means we have to redouble our efforts.

I will tell you a little story that kind of answers this question. Many years ago, I went back to my hometown for my grandfather's side called Tarlow in Poland. I went there for the Rededication if the cemetery. What happened was a Polish doctor moved into the town and he found out that not only did Nazi Germany murder all the Jews in the town and desecrate the cemetery, but the cemetery had fallen to such decay that it virtually disappeared from the map. And this Polish doctor felt that it was his duty and his responsibility to try to restore the cemetery. He went from door to door knocking on people's doors to see if he could find pieces and slabs and fragments of the cemetery that once existed in a small, tiny little town in central Poland. And finally, after 10 years of working hard, they managed to rebuild part of the cemetery to pull the gate around the cemetery and put some of the slabs in a kind of an artistic formation.

Eli: When I was there, I asked him: Dr. Curlyo, what prompted you to do this? And he said, because I felt such a terrible sadness with the fate of the Jewish people. Adn I'm a doctor, but I don't want to just heal people - I want to heal, want to heal wounds of society. So, I decided I'm going to make this my life's mission.

And just then a young girl came over and said, I found another slab of a Jewish tombstone in a barn. Can I bring it over the next day? And I looked at him and said, Dr. Curlyo, isn't this amazing what you've done? You've restored a Jewish cemetery; you brought all these people together to this re -dedication.” How do you feel? Do you feel pride? What do you feel? And he said, “I feel I have to gather even more stones. I feel I have to gather even more stones.”

So when you're asking that question, there's still a lot of work that has to be done, but we cannot shirk from the task

Matt: Well, and we see the need for that work. Right now in terms of as you and I are talking, there has been a huge increase in antisemitism here and around the world. And I just wonder what in 2023 we're starting a new year, what that tells you about who we are and the state of who we are.

It tells us that in every generation we're going to have to fight the fight anew. That in every generation there's going to be forces of evil that rise up and try to get history to repeat itself.

And I'm reminded of a story of a Holocaust survivor (Clara Knopfler) who was with her mother. She was a teenage girl, and she was digging a trench with her mother. And her mother became quite ill and started to kind of become a little bit relaxed on the job. And suddenly, this 15-year-old boy who was a member of the Hitler Youth, because towards the end of the war, the Nazi started running out of men. So, they were taking teenagers to enforce their terrible cruelty.

And this 15-year-old, started beating her mother, and she came out of the trench and said, “how could you do that?”

“How could you beat my mother? That's my mother. Don't you have a mother yourself?” And this German Hitler-Youth member said, “I have a mother, but she's German.”

Eli: And then he stormed away. But the next day he came back. The next day he came back, and he said, “here's a carrot to help you with your nutrition, and here's a cigarette, it will take your mind off your hunger.” And she realized even to that Hitler-Youth, her words about how the mother had an impact.

So, you know what? There's a lot of antisemitism, a lot of hatred, but drop by drop by drop, we will make an impact even on people like that, in that story the Holocaust survivor shared with us.

Matt: That's a very generous view of where we're at right now, and it's not cynicism. You could see, and it would be understandable, where people would feel despondent by what's going on and feel as though as you said, the work in front of you is doubled or tripled because of the state of humanity and where we're at right now.

Eli: Yes, it's a very challenging question. I'm reminded what Elie Wiesel, the Nobel laureate Holocaust survivor, the writer of a number of incredibly beautiful books and poignant and sad books, Night is among them. He said -and this is not just to Jewish people, it applies to everybody, but he said, in the context of being Jewish:

“To be a Jew after the Holocaust is to have every reason to give up your faith in God, give up your tradition and give up your belief in humanity - and still not to do so. In other words, even though we have all the reasons to give up hope, we must not. We must keep on believing that there is a seed of redemption in humanity that we can tap into anytime.”

Matt: What does that tell you then, just finally, about the importance of the work that you're doing, the importance of the work that has been honored by the Order of Canada?

Eli: Well, I feel so privileged to be having the ability, to be making sure, to make sure that the voice of the survivors are not forgotten.

I remember once I was giving a speech in Montreal and after this program was over, this Holocaust survivor came over and she said: ” as she held my hand and looked into my eyes. Please make sure our stories are never forgotten.

And I think of all the goals of Holocaust education, the ability to tell the stories, to make sure these survivors know their stories of their family's loved ones will never be forgotten, and that the lessons have been learned - has been a great privilege.

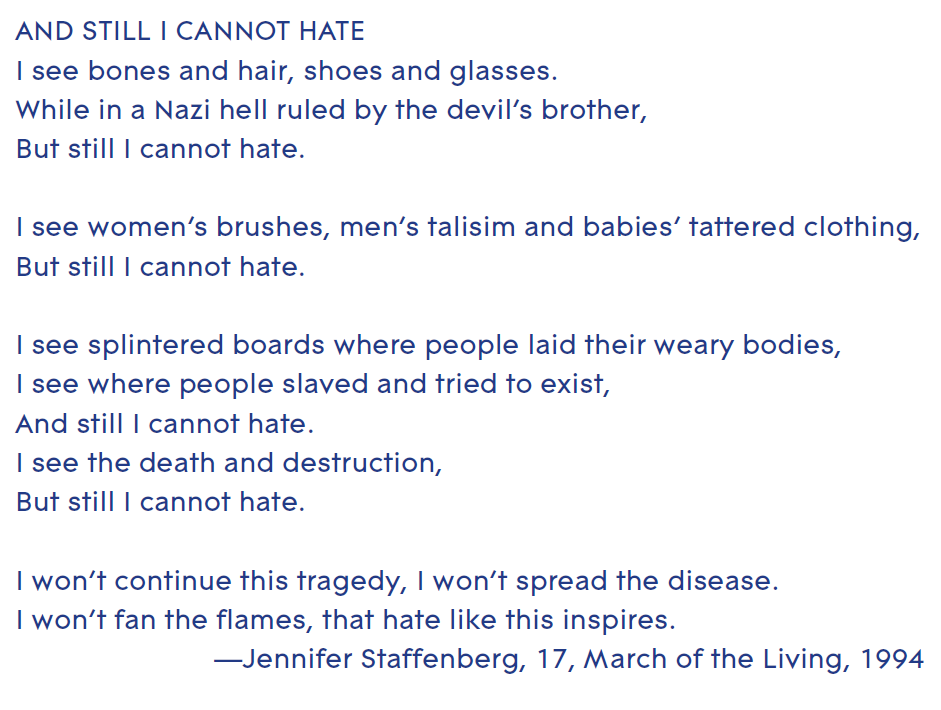

And if I may, can I read you a short poem? One that a student shared with me on the trip.

Matt: Sure.

Eli: Because I learned from the survivors, but I also learned from the students, and this is a poem written by a 17-year-old girl from Vancouver [Jennifer Staffenberg];

After she came back from the March of the Living in 1994, she wrote this poem:

Eli: “Still, I cannot Hate” is the poem, and I think what she's teaching us is that the answer to hate is not more hate. The answer to hate is more love. And the answer to darkness is more light.

Matt: Eli Rubenstein, congratulations on the work that you have done. It's important, but also on the recognition for that work. It's great to talk to you.

Eli: Thank you for this privilege.

Episode 14 WIth Eli: March of the Living & Bringing Polish and Jewish People Together

Dr. Malgorzata P. Bonikowska is a Polish Canadian journalist, broadcaster, community activist, educator, author, and cultural entrepreneur. In all her work, she has been motivated by the objective of building bridges between her two homelands, Poland and Canada. She is the host of Polcast, and the following two interviews were conducted in 2016.

Transcribed from this URL:

https://www.mypolcast.com/2016/07/episode-14/

Malgorzata

For over eight centuries, Poland was home to the largest and most significant Jewish community in the world. The Second World War changed this landscape forever. The Nazis killed 1/5 of the Polish population, 90% of its Jewish population, or about 3 million Polish Jews and approx. 3 million (non-Jewish) Poles.

Today, young Jews come to Poland to visit the camps where the horrors of the Holocaust took place.

The March of the Living is an annual educational program launched in 1988. I'm talking to Eli Rubenstein, Canadian National Director of the March, religious leader in Congregation Habonim in Toronto, author, storyteller, educator, film producer, a charismatic and devoted bridge-builder.

Eli, you have literally devoted your life to preserving the memory of those who perished during the Holocaust. But you don't just dwell upon the past, but you're specifically focused on the future, which is the youth. This mission is closely related to Poland, with which you have very close contacts.

Eli

When I started off my journey in Holocaust education, I really didn't have any preconceived notions about Poland, and so I didn't come with any of the prejudices that sometimes my fellow Jewish participants in the March of Living might have had – which some of them and some of them did not?

You know, throughout our life journeys, we learned different things, and one of the things you learn to do is this: whenever you hear an assumption, to question and to check it out and to find out what is the real, true story.

Since the beginning of the March of the Living, myself, along with the March of the living, has really transformed from a unidimensional program, which was solely to focus on the Holocaust, has broadened in several important areas.

The first important areas broadened is to understand what the Polish people went through, that while the Jewish people suffered a tremendous, tremendous loss during the Holocaust, the Poles suffered tremendously as well, and to appreciate their sacrifice and their history.

That's the first revelation that began to happen in the early 90s, or mid-90s.

The second thing that we began to do is also understand the complexity of Polish Jewish relations, both the beauty and the remarkable civilization that centuries of Jewish life in Poland was able to flourish because of the welcoming, fertile ground that Poland represented in the Jews, but also the difficult parts of that relationship, and to look at both sides with an objective and fair-minded eye.

And the third evolution that happened was also to appreciate the tremendous 1000 years of Polish Jewish history that preceded the Holocaust.

And it's been a wonderful journey.

Subsequent to all of those changes. We also decided the following: whatever conclusion you come to about the history of Polish-Jewish relations, because it's a complicated subject, there is no excuse for not building bridges today. We have had so many experiences, year after year after year, where people in Poland have reached out their hands to the Jewish community, and when we respond, it is something wonderful to behold.

Malgorzata

Practically speaking, how has the program changed so that it serves the purpose of bringing Poles and Jews together?

Eli

Well, I think the first thing is that we really advocate strongly for the meeting of Polish and Jewish youth together. We understand that you cannot hate somebody if you know their story. And we also see that among the young people--within minutes, as soon as you put young Polish teens and young Jewish teens from Canada together in a room--or teens from any background - all of a sudden, they're talking, they're having good time, they're laughing, they're singing songs to each other.

They automatically start to click with each other, and that's the perfect Polish Jewish dialogue.

I will never forget this. I remember a young girl from Montreal, probably in early 20s, from McGill University standing up after a session of Polish Jewish interaction. She said," I came to Poland wanting to hate you, but after meeting you, I can no longer do that." Just that alone that one moment alone is worth, you know, hundreds and hundreds of Polish Jewish dialogue sessions.

They automatically start to click with each other, and that's the perfect Polish Jewish dialogue.

I will never forget this. I remember a young girl from Montreal, probably in early 20s, from McGill University standing up after a session of Polish Jewish interaction. She said," I came to Poland wanting to hate you, but after meeting you, I can no longer do that." Just that alone that one moment alone is worth, you know, hundreds and hundreds of Polish Jewish dialogue sessions.

And so, when these young students meet a Polish Righteous Among the Nations, first of all, this is likely the first and last time that's going to happen. But secondly, in front of their eyes, they see somebody who risked their lives, often to save total strangers, and the look of appreciation and love and gratitude on the faces of these young people, where they're meeting a hero.

Jerzy Kozminski, centre, hid 13 Jews during the Holocaust. He met with Canadian students in Poland who travelled there on a recent trip of the March of Remembrance and Hope. With him, from left, are Alyssa Idler, Carolyn Bartlett, Tashauna Reid and Nahayat Tizhoosh. Photo: Canadian Jewish News

They're meeting somebody who was in such stark contrast everything they have been seeing: the death camps and the piles of shoes and the ashes and the air and the killing fields,

It opens up a whole new area---first of all, of individual appreciation, appreciating the person for who he or she. But also understanding: Wow, there are people like that in Poland who did things that I may not even be able to do, and whatever stereotypes they might have had certainly begin to crack at that during that interaction.

And the third thing I said, which isn't necessarily focused only on Polish Jewish relations, is to take the young people to the Poland Museum of the History of Polish Jews, and to expose them to the 1000 years of glorious Jewish history that that existed, and it existed in Poland more than any other country.

And I'll tell you something funny, because often when I lecture on Polish Jewish relations, I play a trick on my audience. I say, "so which country had the largest population of Jews for the for more years than any other country in the last 1000 years?" And of course, the country is Poland. People say yes. And I say, that's because, you know what that is? That's because Poland was the most anti-Semitic country in the world, right?

And there's a pause, what? What did he just say? Because they've heard that sometimes that Poland the most antisemitic country. And then I just juxtapose it with the fact that this is where most Jews lived and flourish for and all of a sudden there's that realization, this is a complex issue, because if it was most handsome in a country, this would have flourished for close to 1000 years, and that's where the dialog, the discussion begins.

Malgorzata

Do you think that Poles and Jews have found a path of understanding after so many years? Do you think there has been clear progress

Eli

Oh, absolutely.

I mean, the historical realities that have made that happen, or at least helped that happen. I mean, I remember the first time I went to Auschwitz in 1989 I barely saw any references to Jewish suffering in Auschwitz if it made reference to Hungarians or Slovakians, or Lithuanians or Belgium, whoever, or people from Holland, it didn't make the reference the fact that they came there because they were Jewish. Of course, in 1989 Poland was still Communist. But since then, in Auschwitz alone, there are remarkable developments in the concentration camp memorial, where, everywhere you go, all the signs are, of course, of Polish and English and Hebrew and the camp, of course, memorializes the Jewish suffering. But it's not just Auschwitz- Birkenau. I've seen so many incredibly moving and touching Jewish memorials throughout Poland, and this is, this is a testament to me what the true Poland is like.

When Communism fell and Poland was able to assert itself as a democracy, . It chose to celebrate its Jewish heritage. It chose to welcome Jewish facts. It chose to forge ties with Israel. And in Europe today, Poland is one of Israel's strongest allies. So, I think, I think, yes, I think it's moving very much in the right direction. Is there is still antisemitism Poland? Absolutely, there is still antisemitism virtually everywhere in the world.

But I think there's been some dramatic changes over the last 30 years, almost 30 years. And I think the fall of Communism is what, what propelled Poland on the path where it could assert its true identity.

Malgorzata

You will hear the second part of my conversation with Eli Rubenstein in the next episode of POLcast.